By Monica Rodriguez

Published December 20, 2014 Inland Valley Daily Bulletin

Saray Castrejon has been driving for 13 years and pretty much knows the rules of the road. But as an undocumented immigrant, she’s got nothing to show for it.

She has no driver’s license, and she’s not alone.

Castrejon and many immigrants like her hope that will change starting Jan. 2, when a new state law — Assembly Bill 60 — takes effect.

Under the law, which Gov. Jerry Brown signed last year, undocumented immigrants who can prove their identity and that they live in the state can visit a state Department of Motor Vehicles office and apply for a license.

And that’s got Castrejon and unlicensed immigrants from Los Angeles to San Bernardino signing up for study groups organized through community organizations, churches and consulates across Southern California. Through the groups, undocumented immigrants are learning how to apply for and prepare to pass the DMV tests.

The stakes are high.

Fail, and it could mean several months of waiting to take the test again. Or worse, it could mean huge vehicle impound fees. And in the worst cases, deportation, which backers of the law say has torn apart far too many families — for something as simple as not having a license.

Pass, and you’ve got the right to drive in California. And that could mean less fear, and more integration into communities for many, experts say.

REDUCING A DEADLY TOLL

Castrejon is among the lucky ones. Thirteen years. No accidents.

But she’s not taking any chances.

“I haven’t read the (state) driver’s handbook,” she said. “My husband got me a copy, and he has asked me several times, ‘Have you read the booklet?’?”

After taking part in a study group, Castrejon said she was going to take time to study the information in the DMV handbook.

At its core, extending the right to drive to undocumented immigrants is about public safety, officials said.

The bill, introduced by Assemblyman Luis Alejo, a Democrat from the agricultural town of Salinas, cites a DMV study titled “Estimating the Exposure and Fatal Crash Rates of Suspended/Revoked and Unlicensed Drivers in California,” which estimated that 12 percent of California’s drivers do not have valid driver’s licenses.

And those who don’t, according to Brown’s office, were more likely to be involved in fatal crashes than drivers with valid licenses.

The legislation’s backers — ranging from LAPD Police Chief Charlie Beck to Los Angeles Archbishop Jose Gomez to the insurance industry — say training, testing and insuring those drivers can reduce the deadly toll on the state’s roads.

Getting a license means taking DMV tests — written, visual and behind-the-wheel.

The DMV is gearing up — big time — for the estimated 1.4?million undocumented immigrants expected to apply in the next three years.

The DMV opened a new office in Granada Hills just to help meet huge demand. That was one of four that opened across the state, including Lompoc, Stanton and San Jose.

Once issued, the license will look much like the card that goes to citizens and legal residents.

It will have name, picture, expiration date, address, birth date and basic descriptors.

The difference for Castrejon and her fellow immigrants is that it will read “Federal Limits Apply” on the front of the card, and “Not acceptable for federal purposes” on the back of the card.

Those limits mean the license-holder is not entitled to vote or to serve on a jury.

After months of public workshops, the DMV in November released an extensive list of documents that applicants can use to prove their identity, if an applicant doesn’t have proof of ID — ranging from passports to education certificates.

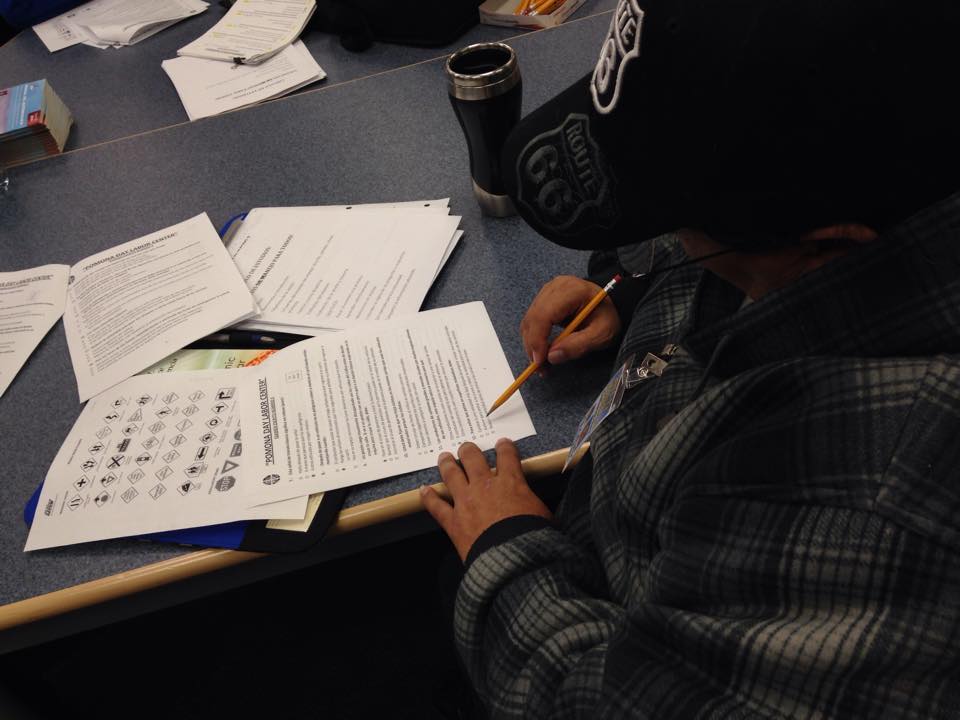

As the application date draws near, a sense of urgency is setting in among some of those attending study groups like those in Los Angeles and San Bernardino, where for months day laborer centers, consulates and local classrooms have been hubs for learning about the written DMV test.

Benjamin Wood, an organizer with a day laborer center in Pomona, is seeing it at the study circles he has organized.

As people talk to friends or relatives who have attended a study circle and have learned about the type of questions they’ll be asked to answer on the test, they begin to feel less confident about their knowledge of driving regulations, Wood said. That, in turn, prompts them to seek help to get ready for the test, he said.

Wood, whose center has been working with immigrants for the past three months, said preparation includes how to book an appointment, knowing the rules of the road and forums with guest speakers from law enforcement and the DMV.

In Los Angeles and San Bernardino, the Mexican consulates plan to offer study guides and workshops, at least through February, officials said.

Interest is clearly spiking.

From Nov. 12 to Nov. 30, 378,891 driver’s license appointments were made, said DMV spokeswoman Jessica Gutierrez. In the same period in 2013, a total of 175,911 driver license appointments were scheduled, she said.

DMV officials believe most of the increase this year is because of AB 60 applicants.

Along with the rush to be ready for the test is a coinciding push urging new licensees to get insured.

“It’s absolutely essential they get insurance,” said Insurance Commissioner Dave Jones, adding that the state’s low-cost insurance program offers policies for low-income people under legislation introduce by state Sen. Ricardo Lara, D-Long Beach, that allows undocumented immigrants to enroll.

Under that legislation, barriers for applicants have been removed, including a requirement that an applicant for the insurance program have a record of three years of good-driving experience.

The insurance requirement, officials say, is every bit as important as the license itself.

‘OUT OF THE SHADOWS’

The study circles foreshadow what Brown and other leaders suggested when he signed the bill in September 2013 — that a law extending the legal right to drive would not only promote public safety but would prompt undocumented immigrants to come out of the shadows.

“When a million people without their documents drive legally and with respect in the state of California, the rest of this country will have to stand up and take notice,” Brown said in a news releaseat the time. “No longer are undocumented people in the shadows. They are alive and well and respected in the state of California.”

Indeed, unlicensed, undocumented persons drive for only the most critical activities, such as going to and from work or to purchase groceries, said Melissa Keaney, staff attorney with the National Immigration Law Center in Los Angeles.

Having licenses will allow these same people to be more active in their children’s schools, in their neighborhoods “and in other things that may promote integration” in their communities, she said.

In the meantime, the law’s supporters can look to the experience of a handful of other states that have passed similar laws for how the future may look after Jan. 2.

Nevada is among those states.

“In the first months or so, we had very high failure rates,” said David Fierro, spokesman for the Nevada Department of Motor Vehicles, which began issuing driver authorization cards, as they are known there, in January.

As many as nine of every 10 applicants failed the test.

It didn’t take long before the message to study hit home. The average failure rate for a license has come down to 57 percent, he said.

“The message that, ‘Hey, you have to actually study,’ got out,” he said.

Castrejon is ahead of the curve, from the looks of things.

A recent study circle was reviewing a question on the use of headlights in foggy driving conditions. A woman said high beams should be turned on in such conditions — and many in the class agreed.

Not Castrejon. Not in this particular case, she said.

“You have to use your low beams because the high beams can blind drivers in opposing traffic,” she told the class in Spanish.

She was right.